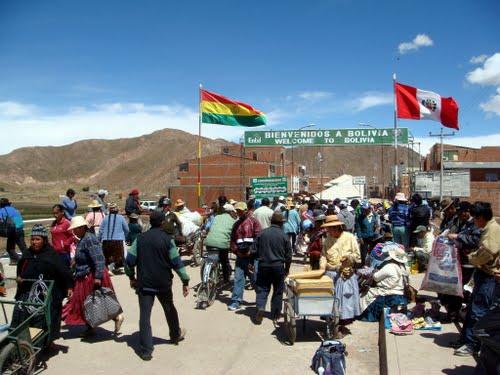

Border Crossing

I knew I was screwed before I even got on my bus. One

hundred and sixty dollars? I thought it was only one hundred and forty!

My bus conductor stared at me expectantly. Mumbling, I reassured her I was completely prepared to get my visa at the Bolivia-Peru border. “Okay. But if you don’t get your visa on time the bus will leave without you.” Normally I would panic and fret, but seeing as how it was still three hours to the border I took a stress nap while our bus wound around sapphire-blue Lake Titicaca towards Copacabana.

My bus conductor stared at me expectantly. Mumbling, I reassured her I was completely prepared to get my visa at the Bolivia-Peru border. “Okay. But if you don’t get your visa on time the bus will leave without you.” Normally I would panic and fret, but seeing as how it was still three hours to the border I took a stress nap while our bus wound around sapphire-blue Lake Titicaca towards Copacabana.

The problem wasn’t simply that I had to pay to get into

Bolivia. The problem was that I also had to pay to leave Peru. I’d spent eleven

months living and working as a volunteer in the San Martin region photographing

and recording native tribes. I stayed eight months past my tourist visa which

meant at a charge of one dollar a day I owed the Peruvian government roughly

two hundred and forty dollars as well as a decent excuse.

For anyone familiar with border crossings they’re not

normally stressful. I envied the Canadians and Brits surrounding me as they

stamped out of Peru and stamped into Bolivia. Only my government, I complained,

would have a contentious relationship with the beautiful Andean nation. The

line filed ever-onwards with me swept up into it’s lazy-river current.

At the Peruvian exit desk the border agent eyed me. “You’ve

stayed way past your tourist visa.”

He raised an eyebrow at me. Dry-swallowing I humbly blushed

and smiled back. “Yes sir.”

He had to pull out a

calendar and calculator to figure out just how many dollars I owed the Peruvian

government. Meanwhile, the bus driver loomed over our bus group as a Polish

woman walked in and out of the office, getting her exit visa in what felt like

an eye blink.

I handed him the two hundred and forty three dollars owed as

well as my Andean card stating my initial entry. He looked up at me as I

watched another of my group move from the Peruvian exit line into the Bolivian

entry line. Sweat hadn’t formed on my brow, but my hand wouldn’t stop shaking.

I could get deported, I rationalized.

“What were you doing in Peru for so long?” The customs

officer asked me.

“I’m not going to lie sir. I was working as a volunteer in

northern Peru and- “I began in perfectly accented Spanish. (You don’t spend

eleven months in Peru without learning the language. At least I had that going

for me.)

“No no no.”

He raised a hand out to stop me. My throat constricted. I

surmised my excuse wasn’t valuable enough to free me from the bureaucratic

chains. I was going to be sent back. At least I still had some Peruvian

currency to take care of my needs, I thought. My visa money could be put to

use. I wasn’t totally screwed.

“You met a beautiful Peruvian woman and decided to stay an

extra couple months for love.” He nodded contentedly. In the space of a pregnant

pause I realized what he was saying. I nodded vigorously.

“Yes sir! Absolutely sir!” He stamped my exit visa. I let out a half-deep sigh. The first part was over with. I even let out a stress-laugh. Love, it seems, had literally set me free.

What happens if you exit one country, but you can’t enter

another country? Do you technically exist outside of international laws? I

pondered this as I hopped in line to enter Bolivia.

This part of the process I had prepared for. I had all my

paperwork: my shot record, the visa application filled out, a passport-sized

photo, and something close to the amount of money I needed. While in line I

kicked myself for not withdrawing more money from the ATM the night before. I

counted my money while in line. One hundred and sixty dollars exactly. Not a

penny more. I let out the other half of my deep sigh.

The visa office called me forward. I presented everything.

The agent smiled and nodded. This wasn’t the first time an American had applied

for their visa while on the border. Over my shoulder I could feel the burning

gaze of my bus conductor. Her attention singularly focused on my exposed back

through the clay walls of the customs office.

The Agent filed my paperwork. They took their own photo of

my smiling face. The process was flying by. No calls were made to the American

consulate. No bag inspections occurred. Easy as one-two-three. I found myself

humming the Jackson Five’s tune and laughing at the bus driver for rushing me.

The elation I felt at successfully navigating the labyrinth of paperwork in

such a rapid manner bubbled through my entire system. I must be some kind of

backpacking hero.

“I’m sorry we can’t accept this bill.”

The earth stopped moving.

“Do you have a different bill? They have to be free of wrinkles and tears.” The agent continued.

The earth stopped moving.

“Do you have a different bill? They have to be free of wrinkles and tears.” The agent continued.

No. Shit.

“Unfortunately it’s Sunday and the banks are closed. You will have to try the money changers.” He suggested. I raised a pointer finger.

“Just- hang on. One second!” I dashed outside with my ever-so-slightly-torn

twenty dollar bill.

Every money changer gave the same story. They had too many ripped bills. They couldn’t trade one of my bills for one of theirs. Please, I begged, if I don’t get a clean twenty then I won’t get into this country. I had already given up all my money, I said. If this didn’t work I’d be left at the border with no money, no entry visa, and no means of getting back to anywhere. Existing in a bureaucratic purgatory between two countries was my backpacking nightmare. Sorry, they all said, they just couldn’t make that trade.

With no other choice I walked up and down the line of entering tourists. I explained my situation to them. Several Canadians stopped and empathized. They offered to pay in Canadian currency. No use, I explained. I’m American so it has to be dollars. Two British women in front of me turned around.

Every money changer gave the same story. They had too many ripped bills. They couldn’t trade one of my bills for one of theirs. Please, I begged, if I don’t get a clean twenty then I won’t get into this country. I had already given up all my money, I said. If this didn’t work I’d be left at the border with no money, no entry visa, and no means of getting back to anywhere. Existing in a bureaucratic purgatory between two countries was my backpacking nightmare. Sorry, they all said, they just couldn’t make that trade.

With no other choice I walked up and down the line of entering tourists. I explained my situation to them. Several Canadians stopped and empathized. They offered to pay in Canadian currency. No use, I explained. I’m American so it has to be dollars. Two British women in front of me turned around.

“We don’t need our money to get in. Would you like to use our twenty?” They

lifted a plastic bag filled with paperwork, passports, and several currencies.

I practically cried as we switched out my bill for theirs. I

ran back into the office, presented the bill. The agent took one look at the

bill and shook his head. That’s when a cold sweat ran down my forehead. The Bus

Driver disappeared. That was a very bad sign.

I apologized and thanked my British friends. Incensed, they

handed me a new bill. I immediately went and offered that to the agent who

smiled, nodded ‘yes’, and finished my Bolivian visa. No relief followed as I

wished my agent to speed up the process of sticking a visa to my passport. The

Bus Driver might, even now, be taking off. All of my hope and money went into

this border crossing.

The moment the agent returned my passport to me I thanked

him and bolted out the door. I slowed down only to thank the British women for

helping me. It was more of a quick shout than anything.

I found my bus. Gasping for breath and sweating heavily I

stepped up on to the bus steps. Inside, barely a quarter of the bus was full.

People continued filing through customs. I lowered my backpack onto my seat and

sat there breathing through all the angst. The tension in my body released

slowly, muscles I didn’t even know were tense unclenched.

The ride into La Paz passed in a dreamy state for me. Our

very first stop in town I ran straight to an ATM and withdrew several hundred

bolivianos. Never again, I vowed. Even as I cursed my lack of preparation

pleasure filled my brain.

I smiled as the Bolivin alitplano flew by my bus window. Chatter boiled up within me. The poor Polish woman next to me smiled her way through all the menial conversations I could invent, stress practically pouring out of my mouth while I spoke. As adrenaline faded and the sun set my eyes closed of their own accord. I slept while my bus twisted and turned it’s way into La Paz. That was how I almost got stuck at the border of Bolivia with no money in my pocket and no way of getting home. That was how I became, in my own eyes, a backpacker en veritas.